Patent Medicines: they claimed to cure everything-- Worthless or harmful but a boon for advertising

A colorful cardboard box in the Laramie Plains Museum (LPM) collection is labeled “Kickapoo Indian Guide to Health and Longevity.” It’s not clear what was originally in the box; it did have some cut-outs of “Indians,” their horses, tents and blankets that would have appealed to children. Possibly it once had some of the “herbs, barks and roots” advertised on the box as remedies.

Not real “Indians”

Turns out that the Kickapoo herbal concoction was made in New Haven, Connecticut; there was nothing “Indian” about it except the name. There is a real Kickapoo tribe that ultimately landed on an Oklahoma reservation, but it gave no medical secrets to the New Haven company.

The Kickapoo name caught the fancy of John E. Healey (1844-1921), a Civil War drummer boy who became a door-to-door salesman of liniments. He teamed up with another peddler and developed “Kickapoo Indian Oil” and other products like Kickapoo Indian Sagwa. None other than the “Hon. Wm. F. Cody” claimed that “Kickapoo Indian Sagwa” cured him of malaria. He said it was “better than quinine,” though quinine has been known for 400 years as an effective malaria treatment. An endorsement by a celebrity or unknown user was a typical sales ploy for marketing worthless medicines in the Victorian era.

“Kickapoo Indian Sagwa” was mainly a powerful laxative, but that was fine with Americans of the late 19th century who thought that cleansing the intestines was a good way for ridding the body of lots of things that might cause illness. The Kickapoo promoters advertised that it would cure “constipation, liver complaint, dyspepsia, indigestion, loss of appetite, scrofula, rheumatism, chills and fever or any disease arising from an impure blood or deranged liver.”

Another quack medicine promoter was Clark Stanley, who excited visitors at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago by cutting up rattlesnakes and putting a piece in every bottle of his “snake oil” cure-all. A 1915 analysis of the contents showed no snake oil; Stanley was fined $20 by the U.S. government, as reported in 2015 by the British Pharmaceutical Journal.

Medicine shows

Another way that “patent medicines” were marketed was through traveling medicine shows. At its heyday, the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Show had 75 to 100 different troupes on the road at the same time. They concentrated on the area east of the Mississippi from Maine to the West Indies, says theatre professor Brooks McNamara in his 1995 book, “Step Right Up.”

As Brooks writes, small towns provided the target audiences, and the shows did feature entertainment which ranged from musical acts to ventriloquists, interspersed with pitches for the patent medicines. Real Native Americans were employed, but they were mostly Iroquois, not Kickapoo.

Perhaps the LPM box might have come from one of those eastern shows. The Kickapoo Medicine Show isn’t mentioned in local papers, but the Kickapoo oil is listed in an ad for the 1915 bankruptcy sale of Laramie’s once-prominent Mills’ Drug and Bookstore at 219 S. 2nd St.

Advertising Pays!

The purveyors of patent medicines were among the first of the nationwide advertisers in America. Some say they provided much of the ad revenue for 19th century newspapers. Most of these ads required would-be customers to contact the company by mail—though the ad might say “found in all drug stores.”

Dozens of these ads, promoting a wide variety of pills, nostrums, and medical devices of dubious effectiveness, are common in any issue of the Boomerang from 1889 through 1910. Some were very dangerous. Among the most lethal contained adult doses of morphine intended for children suffering from colic and teething. They would calm the child, but death could happen, especially if given too frequently. These nostrums were commonly known as “baby killers” by 1900. Only the most naïve customers would buy them, but they stayed on the market.

There was no regulation of what the advertiser could say, so the impossible list of cures claimed by Kickapoo was just one in a world of deceptive advertising. The April 4, 1889 issue of the Boomerang has an ad for “Dr. Haines’ Golden Specific,” touted as a cure for drunkenness, which can be given in food or drink “without the knowledge of the person taking it.” Readers were invited to contact the manufacturer in Cincinnati; it promised that “It never fails.” If it contained morphine, it too, would put the consumer to sleep, possibly before imbibing alcohol. If lucky, he or she would wake up to drink another day. Of course they didn’t say how long the cure would take; a complaint of failure would be countered with: “not enough time has gone by.”

Ayer’s pills

One pill that continued to be advertised through 1920 was for Ayer’s Cathartic Pills. An ad in the January 3, 1910 Boomerang says “…Better stir up your liver a little! Not too much, just a little, just enough to start the bile nicely. Sold for over 60 years.” A recent analysis of some of these pills in the collection at the National Museum of American History determined considerable amounts of aluminum and other metals, along with herbs. The pharmaceutical scientists were looking for really harmful poisons, or radioactive ingredients found in some quack medicines, though none was found in Ayer’s.

Notably, there was a real “Dr. Ayer.” According to Wikipedia, he (Dr. James Cook Ayer 1818-1878) “was the wealthiest patent medicine businessman of his day.”

Phony doctors, phony patents

Of particular annoyance to the fledgling American Medical Association (AMA) was the proliferation of non-existent doctors in patent medicine ads. The real Dr. Ayer was legitimate, (though his drugs weren’t), a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania. Laramie’s Mills’ Drug carried 16 different medicines with the word “Dr.” in the name—for sale at bargain prices in 1915.

Controls on what could be sold were virtually non-existent in the 1880s; people bought rat poisons and medicines from “drug” stores—where all manner of chemicals were sold. A doctor’s prescription was a recipe for the druggist to compound something for the patient from raw ingredients on hand. The mortar and pestle became the drug store symbol.

The word “patent” implies that the U.S. Patent office had determined that a product was effective, but most patent medicines were not patented. To do so, the manufacturer would need to say what the product contained. To admit to a high proportion of water or alcohol would alter the sales potential or give away secrets, so in the Victorian age, use of the word “patented” was avoided. Manufacturers relied instead on heavily advertising their brand name.

There was an exception. Mrs. Lydia E. Pinkham’s vegetable compound for female complaints may actually have been granted a patent in 1875, as a publication of Arizona State University suggests. Something by that name is still sold at Walmart today, though it has no resemblance to the alcoholic medicine Mrs. Pinkham first concocted in her kitchen.

In spite of the lack of patenting, the Victorian public tended to think of drugs they sent away for or bought locally as patent medicines. Informed people did call them “quack medicines” but the naïve consumer did not, and the term “over-the-counter” had not yet gained traction.

Almanacs

Among all the methods of promoting patent medicines, the almanac was the most ubiquitous. The drug manufacturers found that producing a colorful almanac and making it available free got their advertisements in millions of American homes. Dr. Ayer, for instance, spent $140,000 per year on advertising. He published 5 million copies annually of an almanac to push his concoctions.

These popular folk publications reached exactly the people that the medicine pushers wanted to target—rural Americans who might not have much else in the home to read. A new almanac needed to be purchased yearly, and they were known for having hints for home remedies for illnesses that a patent medicine maker could exploit.

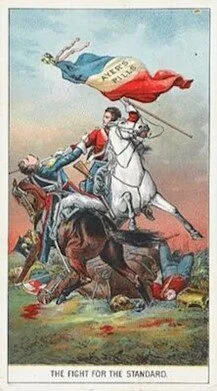

Color printing was an innovation that came along at just the right time. Trade cards with attention-getting images became popular—subtly or overtly carrying a message for medicines. A particularly outlandish trade card was distributed to druggists who carried Ayer’s Pills. It shows a rider on a white horse about to decapitate another opponent. Customers collected them to place in scrapbooks, use as bookmarks or as children’s playthings; so people held on to them.

Pure drugs: kerosene and linseed oil

When patent medicines mentioned in the 1915 ad for the bankruptcy of Laramie’s Mills’ Drug were examined, there were 83 listed by brand name, and about 50 more with the Rexall name. Ten of the 15 medicines with “Dr.” in their names were checked; all were labeled fraudulent by the AMA. “Ballard’s Horehound Syrup” in the Mills’ ad, for instance, made claims that were “knowingly and in reckless and wanton disregard” and fined $10. Another product from the same manufacturer, “Ballard’s Wonderful Golden Oil,” claimed to cure diphtheria and whooping cough but was found to contain 96 percent linseed oil. For that product, the manufacturer was also fined $10 in 1915.

By requiring almost nothing more than full disclosure of ingredients, the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act did put some of the worst offenders out of business. Progress was slow, the 1921 AMA publication “Nostrums and Quackery,” lists well over 100 brand name patent medicines as fakes, with descriptions of court cases and fines paid by the manufacturers. But the pittance of the fines left many still on the market before druggists and consumers realized that they were being swindled.

The drug Addiline, for instance, as disclosed by the AMA, claimed to be a cure for consumption (tuberculosis) and was still on the market in 1920. It was found to contain a large proportion of kerosene, a smaller amount of turpentine, and nothing else, except a small amount of aromatic oil. The chemists said that it would make a better furniture polish than tuberculosis remedy.

False hopes

Abbott’s Rheumatic Cure was sold in Laramie, and the manufacturer, Turnock Medical Company of Chicago, took in $350,000 annually, with its fraudulent medicines based on the theory that all diseases were caused directly or indirectly to excess uric acid. In 1914 the Postmaster General banned all mail-orders sent to Turnock, which was upheld when the company appealed.

The tragedy was that fraudulent patent medicines like these provided customers with nothing but false hopes. This might then cause them to fail to seek treatment from real doctors who might have been able to help. The patent medicines could also do worse damage to the patient’s system than the disease they hoped to cure—if drinking large amounts of kerosene could even be tolerated. Miracle “cures” for many diseases didn’t happen until antibiotics and vaccines were developed.

By Judy Knight

Source: Laramie Plains Museum

Caption: Box that once contained Kickapoo Indian Remedies of “Herbs Barks and Roots,” promoted by Buffalo Bill. “Indian” in the title was exotic and customers fell for the possibly secret cure, but virtually all were fakes

Source: www.tradecards.com

Caption: Trade Card for Ayer’s Pills, a laxative patent medicine printed sometime between 1870 when color lithography became commonplace, and 1900 when the trade card fad died out.