Your mail was delivered by carrier today! Fresh off the eastbound train.

Laramie was born in the spring of 1868, when Union Pacific Railroad crews arrived with their entourage of gamblers, hustlers, saloonkeepers, and ladies of the night. But it wasn't long before signs of civilization began to appear. Just two years later, a literary society and library were established, and Louisa Swain made political history when she voted on September 6. In 1874, the Grand Opening of the Laramie Opera House was a resounding success. No doubt Laramie would soon be a booming metropolis!

But twenty years later, mail service—key to community health—remained primitive. Residents and businesses were forced to go to the post office just to find out if they even had mail. All agreed Laramie deserved better. Information and news were of great import then, just like today. Letters were the era's text messages and tweets.

Connecting the nation

In 1775, our de facto national government—the Second Continental Congress—was focused on winning the Revolutionary War. Toward that end, a system for secure delivery of letters and intelligence was created under the leadership of Pennsylvania delegate Benjamin Franklin, who was Postmaster for the Crown until he was fired for colonial sympathies. After the Declaration of Independence in July 1776, the system and Franklin became the new nation's postal service and postmaster.

After the War, demand for postal service did not slow one bit. Instead, it increased at an ever-accelerating pace. The nation was expanding by leaps and bounds—into the Midwest, up and down the Mississippi River, west to the Rocky Mountains, and then to the Pacific. Between 1790 and 1860, the population grew from 3.9 million to 31.4 million, an eightfold increase. During that same time, the number of post offices increased 380-fold—from 75 to 28,498!

Why this great disparity? Because in battles over spending that accompanied the nation's growth, advocates for improved communication generally won. When territories, states and communities petitioned for mail service, they usually got it, regardless of cost. Connecting the nation had become the Post Office Department's top priority.

We also want speed & convenience

One factor in the postal service's skyrocketing popularity was innovative use of technology, especially "Mail by Rail." U.S. railroads were designated postal routes in 1838, but it was the rapid expansion of rail lines after 1860, coupled with efficient use, that gave wings to the mail. Railway Post Offices, introduced in the 1860s, greatly accelerated delivery. In specially-designed cars on high speed passenger trains, postal staff sorted mail as they criss-crossed the country.

Greater convenience was another goal. Before 1863, "delivery" meant from post office to post office (a few cities offered home delivery for one or two cents more). Then in July of that year, free home delivery was introduced in large cities.

Not surprisingly, it was hugely popular and in great demand. Communities could petition for free postal delivery if their population was at least 10,000, and annual postal receipts greater than $10,000. Additional requirements included sidewalks and crosswalks, streets with names and lights, and a numbering system for buildings.

Will Laramie be among those selected?

Free postal delivery arrived in Wyoming Territory in 1887, but only in Cheyenne. On August 6, the Cheyenne Daily Leader, arch-rival of the Laramie Boomerang, was beside itself with pride, proclaiming: "Cheyenne is beginning to put on all the frills of a full-blown metropolis." The Boomerang took this in stride. "At the present rate of growth that marks Laramie, this city will be entitled to free delivery inside of two years."

Three years later, in 1890, Laramie still was without delivery service, but there was hope. In October, N.E. Corthell reported to the Board of Trade (chamber of commerce) that Congress had allocated $10,000 to test free delivery in towns with populations between 5000 and 7000. The Board and the Boomerang both were confident that Laramie would be selected. "Cheyenne already has free delivery and Laramie is the next town of importance in the state, and each of the new states will at least be given one test town."

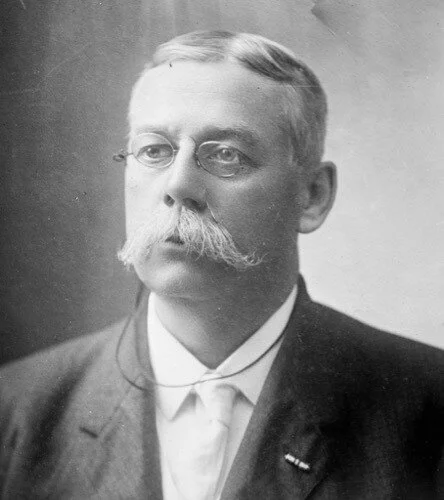

November 7 brought more good news: "Very Encouraging Outlook for a Trial of the System." W.D. Thomas, Secretary of the Board of Trade, happened to be an old friend of John Wanamaker, the nation's Postmaster General. When Thomas contacted him about delivery service in Laramie, Wanamaker expressed interest, requesting more information—such as whether one carrier would suffice.

Unfortunately, Corthell's report was not entirely correct. To be eligible for the trial, a town had to have 300 to 5000 residents. Late in November, the Board of Trade received official notification that Laramie was too big. However, because postal receipts were close to $10,000, it should qualify under the regular law.

Try, try again

In early 1891, systematic numbering of houses and businesses had begun. "Laramie is expected to have the free postal delivery system established during the coming summer,” announced the Boomerang. Annual postal revenue currently was $9849.81. Surely it would reach the required $10,000 "if Postmaster [Richard] Butler receives his supply of stamps in time. He is almost out."

In June there was another delay, due to other unmet requirements. Mail deposit boxes needed to be installed across the city, and the post office still lacked work space for carriers. Postmaster Butler should "commence a great big rustle at once," advised the Boomerang.

The article ended with an interesting question. "There are many applicants for the three carrier positions, and the number is increasing every day. Among the number are some ladies. How will the ladies wear uniforms?"

Another obstacle looms, to the east

Early in 1892, disturbing letters appeared in the Boomerang, from Wyoming's Congressman C.D. Clark and Senator F.E. Warren. Both noted that Laramie's postal revenue was insufficient for free delivery, though not by much ($150.19). But even if it were to increase, the city likely would be rejected. Twenty communities with much larger populations and revenue were on the waiting list.

Yet Senator Warren ended on an optimistic note. Postmaster Wanamaker had assured him that the small deficit in receipts could be overlooked. And after Warren pointed out he was asking on behalf of just one community in the state, he was given Wanamaker's "honest assurance that Laramie's claim should be considered among the very first when proper means have been secured."

Another obstacle arose five months later. New regulations prohibited funding of additional delivery service in Congressional Districts where at least one city already was so served. In 1892, as now, Wyoming had a single district, and it had a city with free delivery—Cheyenne.

Yet Warren remained hopeful; it seemed impossible to dampen his optimism. "... today at the department, I was assured that ... we shall have early and friendly attention. I feel quite sure tonight of final success and think we will be attended to very soon."

He was correct. In late September, the Board of Trade received a telegram: "Order signed today establishing free delivery at Laramie to commence December 1st, with three carriers. Congratulations. F.E. Warren."

“Your mail was delivered by carrier today.”

On December 1, 1892, at 11 a.m., carriers Chris Dawber, A.B. Pope and Victor Cokefair hoisted their heavy mailbags and left the post office, at 315 S. 2nd St. They were 3.5 hours behind schedule but for good reason. It was the first day of free postal delivery in Laramie. Because they had spent two weeks familiarizing themselves with their districts, they reached without delay all addresses for which they had letters. If no one answered their knock or shout, the letter was returned to the mailbag for future delivery.

Meanwhile, back at the post office, many customers at the General Delivery window were greeted with “Your mail was delivered by carrier today” ... but not everyone.

Limited funding, limited service

Initially, only the main part of Laramie had free postal delivery—from the railroad tracks east to 8th St., and from Clark St. south to Park Ave. In response to complaints, Postmaster Butler explained that districts were designed by the Postal Inspector in Cheyenne. If the program was successful (it was), funding and coverage likely would expand (they did).

In Laramie, interest in and enthusiasm for the postal service and everything it provided was tremendous—evidenced by the lengthy Boomerang article the day free delivery was launched. District boundaries were described in detail, and locations of mail drop boxes listed. The carriers' schedule occupied five paragraphs.

Mail would be delivered Monday through Saturday, each carrier making three rounds per day. This may seem odd given the sizable portion of town excluded from service, but multiple daily deliveries were common nationwide. The goal was to get a letter to the customer's door as soon as possible (like Walmart's Delivery Express).

Starting at 7:15 a.m., carriers made deliveries in the business district via a special route, and collected mail for the westbound train, which departed at 9:35 a.m. After mail brought to Laramie by this train was "overhauled" (sorted), carriers started their second round, at 11 a.m., this time covering their assigned districts. The third and final round commenced at 4 p.m., after mail from the eastbound train and local mail had been sorted and was available for delivery. Each man again covered his entire district.

During this final round, carriers also gathered mail from 18 conveniently-located drop boxes—no longer would it be necessary to go to the post office to mail a letter! A letter could be sent at no charge if the recipient had a box at the Laramie Post Office. Otherwise, the sender attached a 2¢ stamp.

Feel that metropolitan air?

On December 6, 1893, Laramie's carriers and Postmaster Butler gathered at Wood's restaurant for oysters, quail, lobster salad, Zinfandel a la mode biscuits, and much more—to celebrate a year of successful free postal delivery. For a full year, they had sorted and delivered several hundred pounds of mail daily, bringing excitement and disappointment, joy and sorrow, good news and bad to a large portion of the population. "The service has given remarkable satisfaction" reported the Boomerang, as well as providing Laramie with "that additional metropolitan air." It was sure to continue.

By Hollis Marriott

Source: 1894 Original Laramie plat map by civil engineer W.C. Willits of Denver.

Caption: Laramie postal delivery districts with carrier names, as of Dec. 1, 1892. Blue polygons

mark mail deposit boxes, pink arrow points to Post Office. Colored lines, labels and symbols added by the author.

Source: U.S. Post Office; printed by the American Bank Note Company, 1890

Caption: Most commonly used postage stamp in the 1890s, 2 cents for 1st-class domestic postage. George Washington has appeared on more U.S. stamps than any other person.

Source: Library of Congress; Bain News Service, 1919 (Photographer unknown)

Caption: Francis E. Warren, who, during a long career in D.C. until his death in 1929 at age 85, used power and pork-barrel politics to secure millions of dollars for Wyoming.