UPRR Rolling Mills; Once Laramie’s Pride

Laramie’s first recycling plant was one that made new steel rails out of high quality but worn scrapped railroad track.

It was 1875, Laramie had been in existence just seven years, and the new “rolling mill” was a source of civic pride (despite the resulting air pollution). Built by the Union Pacific Railroad, the mill recycled track using significant amounts of water and coal. At first, it probably used wood as the fuel.

It was a sign of progress, a nationally-significant industry that gave employment to local people, whose paychecks helped to sustain the fledgling town of Laramie. Built of native stone quarried locally, the rolling mill was actually attractive architecturally if you could ignore the smoke and soot. It regularly provided employment for over 150 men.

Although the UPRR built it initially and owned the mill, they leased it to several different operators. It lasted from 1874 when construction began, to 1910 when it burned. It was located approximately where the Safeway Plaza on North 3rd Street is today, between Harney and Bradley Streets.

Scrap steel was brought to the mill on rail cars, melted down in the big mill furnaces, and then extruded into rods. While still hot and malleable, giant “rollers” formed the sections into the familiar “I” profile required for train wheels called “trucks”. The heavy-duty rail used by the main line was called “60 pound rail” because one yard of it weighed 60 lbs. Narrow gauge rail, by contrast, weighed about 25 pounds per yard. The weight did fluctuate over the years, depending on economic circumstances.

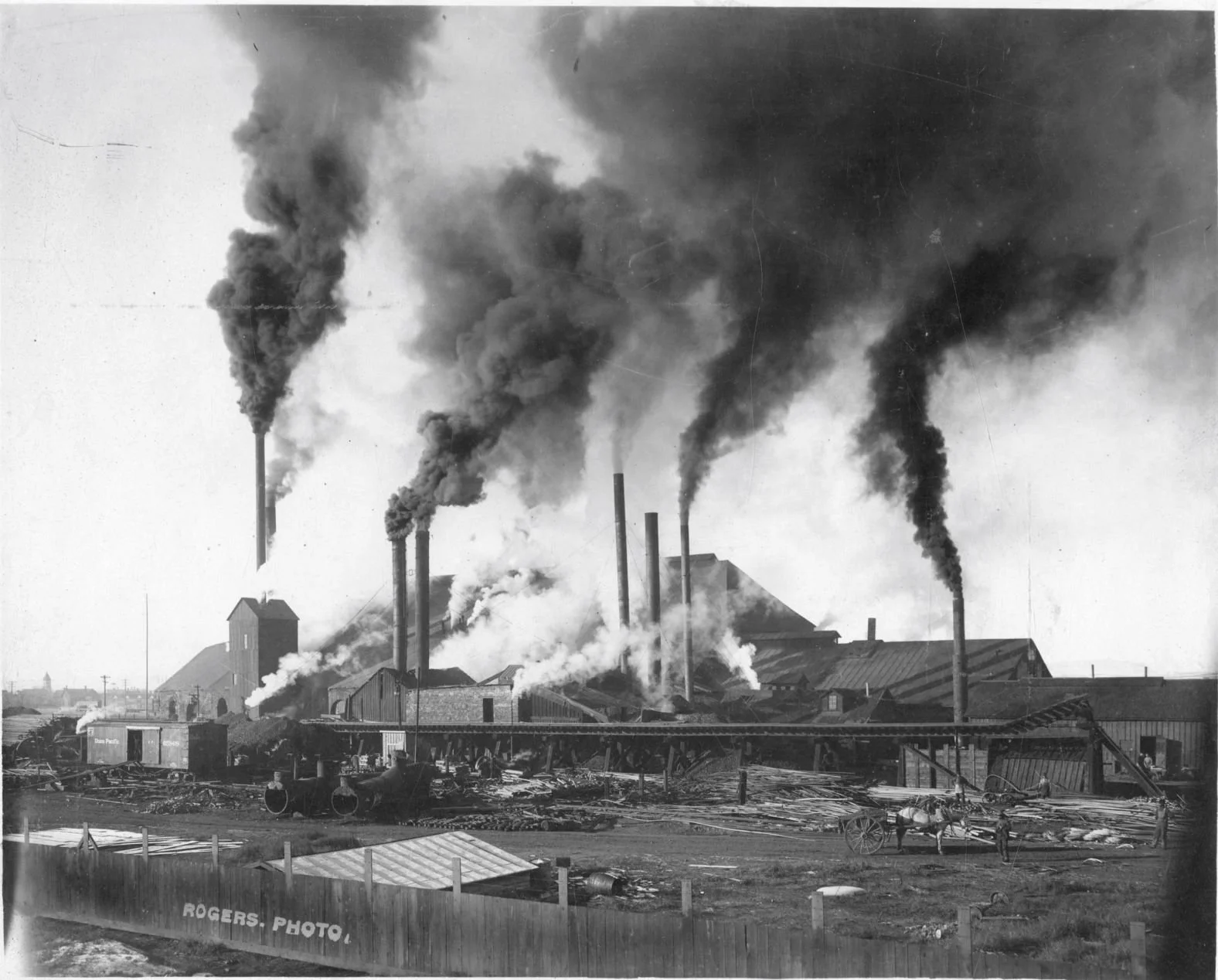

Around 1878, a foundry was added. This enabled the mill to use other scrap metal to make cast iron and steel equipment, including small items like nuts, bolts and spikes. With the foundry addition, by 1908 there were nine smokestacks indicating nine steam engines powering the furnaces.

A hand-painted china plate on display in the Ivinson Mansion shows the expanded rolling mill, with smoke from all nine stacks obscuring the sky. Surrounding this photographic decal are what seem today to be incongruous pink roses and gold filigree. But at the time, it would have been appropriate to show pride in smokestack industry.

Great quantities of water were required to run the boilers for the steam engines. One of the lasting benefits to Laramie of this industry was the development of City Springs east of town. The UPRR laid underground pipe from the springs west down Grand avenue to 2nd Street, then north to Harney Street. There was over twelve thousand feet of twelve-inch wide water line to that project. Around 1875, the city installed connections to the UPRR water line in the downtown area and east on to 6th Street, which was the edge of town then.

An article in Laramie, Gem City of the Plains, edited by Mary Kay Mason, says that the mill required 38 tons of coal per day to power the boilers. Around 1901, there were 350 men employed night and day at the mill, according to a newspaper account. At that time, the operating lease was held by Colorado Fuel and Iron (CF&I), of Pueblo, Colorado. This company was owned then by John D. Rockefeller and partners.

Over the years the rolling mill had been plagued by accidents that cost worker’s lives. The worst of these came in 1876. On March 23rd at 4:30 a.m., Laramie townspeople were awakened by an horrific explosion that shook their homes. Some thirteen months into operation, one of twelve boilers blew up at the Rolling Mill, catapulting through a three foot thick wall, severing an elevated embankment of rail track outside, and landing over two football fields away out on the prairie. A skeletal crew from the graveyard shift was on hand. Had the explosion happened one hour later after shift change, casualties would have been far worse. As it was, four men were instantly killed; four of the injured with bruises and scalding would die within the next day. Of the dead, only Alexander R. Bell, having no family, would be buried in the city cemetery. Five new widows and over fifteen fatherless children were created

Civic leaders attempted to entice the railroad to rebuild after the 1910 fire. However, the operator, CF&I, had a big steel rail operation in Pueblo by then, and the Laramie site was not rebuilt.

By Jerry Hansen

Caption: Remains of the Laramie Rolling Mill after the November 8, 1910 fire that destroyed it. Men are inspecting the wreckage, with a section of the three-foot thick wall built of stone rubble that was about all that remained after the roof burned through. The name “Ware” written on the negative along with the caption indicates the photo was probably taken by Walter E. Ware, who was brought to Laramie by the UPRR as a draftsman/architect for the railroad shops, and may have designed the mill as well. He designed several private homes in Laramie, such as the Ivinson Mansion, before moving on to a prosperous architectural career in Salt Lake City. Photo courtesy of the Laramie Plains Museum.

Rolling mill at full operation. Laramie Plains Museum