"Historically Insignificant” factory site becomes a significant Laramie bridge.

You would never know that the new Snowy Range Road Bridge cuts through property that once was an early 20th century oil refinery and later a factory to produce an obscure element. Almost no trace remains of these forgotten enterprises.

During the spring and summer of 1917, oilman W.M. Armstrong of Rawlins and Denver explored an area about ten miles west of Rock River; he staked out 11,000 acres that looked promising.

Cooper lease pays off

Armstrong worked with a Laramie attorney, Will McMurray, to secure leases from landowners. One they obtained was on ranch land owned by Frank Cooper.

The men approached the Ohio Oil Company about exploiting what would become known as the Rock Creek Oil Field. Ohio Oil began drilling in the fall of 1917 and by the following spring enough oil was produced to make the field commercially viable.

A front-page headline in the Laramie Boomerang on February 21, 1918 announced: “…Oil Rushes into Casing When Drill Touches Outer Crust of Wall Creek Sand—Ohio was Drilling for Will McMurray and W.M. Armstrong who Hold Leases on Field.”

New town near field

To supply the new industry demands, a depot and warehouse were built at the town of Rock River along the Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR) tracks. A large camp was established nearer the oil field.

The infrastructure near the oil well sites included a hospital, blacksmith shops, machine shops and residential quarters for the workers. Initially, the new town was named for the company, Ohio City. Later the town name was changed to McFadden for an oil company executive.

Ohio Oil contracted with the Illinois Pipeline Company to deliver oil to the UPRR for shipment to Salt Lake City.

Midwest Refinery

As this was going on, the Midwest Refining Co. looked to expand its operations in Casper and Greybull into the new oil fields opening in southern Wyoming.

Initially, Midwest intended to build the southern refinery in Rock River. The company sent several rail loads of materials there before learning there was an insufficient water supply from Rock Creek.

The city of Laramie was an ideal second choice for the refining operations as it was also located on the main rail line. The refinery could get plenty of water from the Big Laramie River and the City Springs. An educated workforce and available housing added to the location’s attraction.

A site was chosen along the Laramie River, on both sides of Cedar St., a dirt track then. The site extended north to Curtis St., which was then called Stockyard Road. A high water table discovered as work started in early 1919 briefly delayed construction.

Further testing showed a layer of limestone at a depth of fourteen feet that would make a solid foundation. Building resumed in September 1919, with the heavier structures being supported by caissons drilled into the limestone.

Stills are constructed

The fall of 1919 and the winter of 1920 were brutally cold. The concrete work began in November with over 6,000 cubic yards poured after the gravel was heated and mixed with hot water.

The company reported that the poured concrete was immediately covered with large tarpaulins and heated for two or three days from nearby kerosene heaters called salamanders until the concrete was thoroughly set.

Once the concrete for the first two batteries of stills had been poured and set, large tanks (10 feet in diameter, 30 feet in length) were rolled into place atop the foundations.

There were five stills in each battery, each holding a large furnace where wood was burned to heat the tank above. The exhaust was connected to a 150-foot high smoke stack.

From each still, the ovens would heat oil to various temperatures in order to separate products such as gasoline, kerosene, fuel oil, motor oil, and other petroleum distillates.

When the Midwest refinery was complete, the site included warehouses, a power plant, a business office, laboratory, boiler house and a tank farm. The tank farm was impressive: ten 10,000-barrel and six 35,000-barrel tanks held fuel oil. Also, there was a pair of 55,000-barrel tanks to store the crude oil from the field. Even more tanks were constructed as the plant went into full operation.

Refinery expansion

Beginning in early summer of 1920, another company joined Midwest Refining Company at the site. Standard Oil of Indiana built a second refinery to the south of the Midwest operations. The new refinery consisted of a pair of still batteries, each with nine stills.

These stills were connected via a subterranean tunnel system for heating and ventilation purposes, and were connected to another 150-foot tall smoke stack. With them, the more petroleum products could be produced in Laramie.

“Laramie’s Greatest Industry Will Be Welcomed Tomorrow” was the Laramie Boomerang headline on August 3rd, 1920 as the Midwest and Standard Oil refineries began their twelve-year operation on the northern edge of town.

In the fall of 1920, Midwest Refining Co. also began to expand, adding another battery of six stills and at least three more 55,000-barrel tanks by the end of the year. Within six years, Midwest was operating both refineries, and it was considered to be a single operation, then with around 34 stills.

The end comes

In the late 1920’s, Midwest Refinery Co. was sold to Standard Oil of Indiana. But on April 1, 1932 the new owners announced that the Laramie refinery would be closed.

A reason cited for the closure included what management claimed was poor production, saying the refinery had been operating at a loss for many years.

Some of the 65 employees were offered part-time employment at the company’s Casper refinery. Standard Oil of Indiana hired a night watchman in the event operations resumed.

This, of course, never happened. All of the serviceable machinery was dismantled and removed from the site. Standard Oil of Indiana sold the property in 1940 to Mildred and Dewey Burriss.

A short-lived idea—Yttrium

The Burriss’ apparently left some of the land vacant and may have leased portions to several different small businesses. In 1956, the southeast portion of the former refinery property was sold to United States Yttrium, a small start-up planning to process and refine yttrium ore.

Two Laramie entrepreneurs, chemist I. Wayne Kinney Jr., along with Gene Clark, founded United States Yttrium with some encouragement from the U.S. Bureau of Mines. They contracted with Spiegelberg Lumber Company to construct a processing plant, utilizing the existing furnaces of the original Midwest operations.

Local architects Hitchcock and Hitchcock designed the new building. The plans showed a large tower, with both an elevator and spiral staircase, though neither were installed in the finished building.

United States Yttrium declared bankruptcy in 1957, as a result of technological advancements. Yttrium was going to be used to coat nuclear fuel rods, but zirconium was found to be more efficient.

The property was foreclosed upon in 1960 with a Sheriff’s Deed being issued on July 21st. Over the following decade, the property changed owners numerous times. The old U.S. Yttrium site began to serve as a dumping ground for industrial and household refuse. It also became a haven for street artists and vandals alike.

From approximately 1970 until about 1984, the site was used for several different business concerns, including an automotive junkyard, automobile repair and body shop, a refuse company’s storage facility, and a logging operation. More people became acquainted with the derelict site with its graffiti decoration when North Cedar St. was extended to Curtis St. sometime in the early 1980’s.

Environmental concerns

Beginning in 1984, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality (WDEQ) began testing the soil in and around the site. Their contractors found a large concentration of asbestos-containing materials (ACM) in the area west of Cedar St along the Laramie River where the tank farm had been

Asbestos was not known to be a carcinogen when it had been used originally. It was placed between the tank farm and the refinery to reduce the threat of explosion in the event of fire.

In 1991, the EPA issued an order to the former owner, Standard Oil, (now operating as BP America), to clean up the entire 236 acres of the site.

First, the requirement was to remove the oil/water separator that was contaminated. Next, a 10-inch layer of topsoil was placed on the west side of Cedar Street to help mitigate the ACM. Further abatement was conducted in 2010 when ACM was found along the Laramie River Greenbelt after EPA and WDEQ contractors tested the groundwater and soil around the site.

A bridge helps reclamation

Beginning in late 2012, The Laramie Rivers Conservation District (LRDC) purchased the 5.6-acre parcel of the U.S. Yttrium site with the intention of remediation and possible rehabilitation of the land for offices.

In summer 2014, LRDC began the demolition of the Midwest section of the site, completing the work in about four months in one of the most significant projects ever orchestrated by the local conservation group. Meanwhile, the Wyoming Department of Transportation (WYDOT) made a decision in 2015 on a site for the replacement of the Clark St. Viaduct, which had opened in 1963 and was past its 50-year estimated lifespan.

Using the Harney St. approach from the east, the route required demolishing the former U.S. Yttrium site. The bridge opened to much acclaim for its design in 2018.

Today, the land where these industrial operations were has been successfully reclaimed. Hardly anything is left to reveal what was once between Curtis and Harney Streets and between Interstate 80 and the UPRR tracks. There is a tall fence around the LRDC property, not because it is hazardous, but while it is still vacant to keep it from reverting to the dump grounds it used to be. Much of the southern quarter is completely gone, under the Snowy Range Road Bridge.

By Daniel “Doc” Thissen

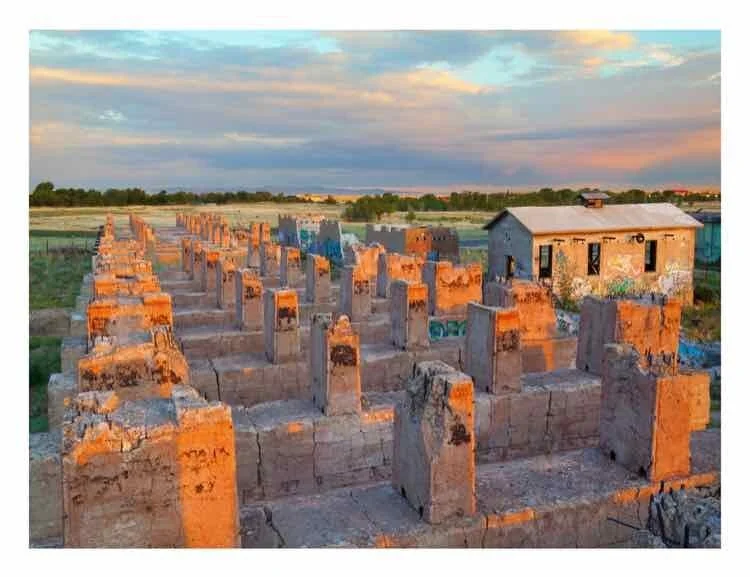

This postcard from around 1920 shows the Laramie Midwest Refinery under construction, with the steeple of St. Matthews right of center on the horizon and the UPRR smokestack on the far right.The view is looking southeast, the tank farm with at least 20 oil storage tanks of various sizes would have been behind the photographer. Cedar St. is in the middle going from left to right, with small cotImage of remnants of the now-demolished Standard Oil stills as they were seen in July of 2013 at sunrise on the east end of the south stills; today the Snowy Range Bridge cuts a path through this location.tages clustered along the dirt road.

Source: Reals Collection, Laramie Plains Museum

Image of remnants of the now-demolished Standard Oil stills as they were seen in July of 2013 at sunrise on the east end of the south stills; today the Snowy Range Bridge cuts a path through this location.

Source: “Doc” Thissen, photographer