Dr. Grace Raymond Hebard, a UW “Giant”

Dr. Grace Raymond Hebard (1861 – 1936) stood head and shoulders above other pioneering women involved with the fledgling University of Wyoming (UW), which opened its doors in 1887. Just four years later, and a year after Wyoming became a state, she began the unusual dual role as paid secretary to the UW Board of Trustees as well as an unpaid member of the board. Her annual salary was $1,800, more than most faculty received.

She had come to Wyoming in 1882, with a new degree in engineering from the State University of Iowa. According to Mike Mackey’s biography of Hebard in WyoHistory.org, she took a short-term draftsman’s job with the U.S. Surveyor General’s Office. That agency was responsible for surveying and mapping the Wyoming Territory. Her widowed mother, sister Alice and two brothers moved to Cheyenne with her.

When the essential mapping was done, the federal staff was greatly reduced and she moved over to the Wyoming Territorial Surveyor General’s Office in 1889 where she rose to the rank of deputy state engineer. By 1891 she had moved to Laramie full time.

Seventeen years of influence

Her highly influential UW position allowed her a great deal of power and, “I used it,” she was credited with saying. There was a new governor of a different political party in 1903 and Hebard was not reappointed as a Trustee. However, somehow she managed to continue as paid board secretary until stepping down in 1908 under some duress.

In a history of UW published for the centennial of UW in 1986, author Deborah Hardy says, “…for seventeen years, Hebard’s influence was all-pervasive, and in terms of the University’s day-to-day operations, policy was often left in her hands.”

There were complaints, mainly that she usurped the role of University president. She may have played a major role in the dismissal of at least one UW president, Albinus A. Johnson in 1896, and possibly caused the resignation of President Elmer E. Smiley in 1903. Professors Justis Soule and Aven Nelson had reasons to resent her—both preceded her as UW Librarian, and had been among the first six UW faculty members, appointed in 1887. Making enemies didn’t seem to faze her; she shouldered on doing what she believed best for the University.

She was the secretary for the Agricultural Experiment Station, responsible for applying for and dispersing federal funds. Sometimes the “experiments” raised federal eyebrows, but though auditors chastised the University on occasion, the funds generally continued and were crucial to keeping UW afloat in difficult times. Her role in bringing in this outside source of funding may have been Dr. Hebard’s greatest contribution to the continuation of UW when it seemed on the brink of folding.

Becomes a professor

Hebard took advantage of correspondence study to receive an M.A. degree from the State University of Iowa in 1885 while she was working in Cheyenne. After she had been appointed to the UW Board of Trustees, she received a Ph.D. in political science from Illinois Wesleyan University in 1893, also by correspondence.

The trustees gave her a professorship when her term as a trustee ended, a fact that rankled some. Simultaneously she became UW librarian and a professor of “political economy.” Along the way she became a passionate history enthusiast. She recognized the value of gathering oral histories from pioneers, and it is from these stories that much of the early history of Wyoming is documented, though some have been debunked.

History professor Dr. Hardy wonders when Dr. Hebard found time to write a textbook on Wyoming history and government—not to mention the four other books she authored or co-authored. In addition, she became the state’s woman champion in golf and tennis and had many other activities including the DAR, the State Historical Society and even served as president of the local camera club.

She was admitted to the Wyoming Bar in 1898, the first woman to be so appointed though she never practiced law. In 1907 she was a member of the State Board of Examiners and was responsible for writing examination questions in geography, geometry, civics, and biology for those who wished to be certified as Wyoming teachers. This role often required her to attend 2-day meetings around the state to conduct and grade the examination papers. By 1919 she was also the Secretary of the State Historical Society.

While still in Cheyenne in the 1880s she became a charter member of the Free Public Library Auxiliary Association. Her 15-year involvement with the UW Library resulted in the first acquisition budget for the library. By 1917 the library had 17,000 volumes and subscriptions to 200 journals and magazines. She retired as librarian in 1919 but lived to see the establishment in 1932 of “The Hebard Room” to honor her collections on western history. Her personal library was donated after her death to expand this collection.

Influential Suffragist

We don’t know if the Territorial Legislature’s act grating women the right to vote in 1869 had anything to do with her coming to Wyoming in 1882, but she was an ardent suffragist.

Dr. Hebard was a good friend of Carrie Lane Chapman Catt, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The two Iowa natives pioneered in receiving college degrees at a time when it was unusual for women. Grace Raymond Hebard began as an activist early on and realized that she also had a knack for public speaking.

After becoming president of NAWSA in 1900, Catt often recruited Dr. Hebard as a speaker who could point out that before becoming a state in 1890, Wyoming women had been voting for 20 years. In 1900, Wyoming was still the only state or territory that allowed women to vote in general elections.

Dr. Hebard also had a flair for the dramatic. She wrote a one-act play about the passage of the Woman’s Suffrage Act that is archived at the UW American Heritage Center (AHC), though we don’t know for sure if it was ever performed.

Dr. Hebard and another UW professor, Dr. June Etta Downey, teamed up to convince the faculty to award the first-ever honorary degree to Carrie Lane Chapman Catt. A photo of Catt, Hebard and a group of other women on the occasion of her honorary degree in June 1921 is posted on-line at ahcwyo.org. It is titled: “The 19th Amendment and Wyoming’s own Grace Raymond Hebard” by UW associate archivist Leslie Waggener.

Americanization

One of Dr. Hebard’s other passions was “Americanization” of immigrants. Her time at UW happened to coincide with one of the greatest influxes of immigrants that America had ever had. She was determined that in Wyoming, at least, these immigrants would learn English and become assimilated into American culture.

She volunteered to teach English and saw to it that classes were established for adults as well as children. She promoted Americanization in speeches throughout Wyoming.

Esther Hobart Morris Myth

Grace Raymond Hebard is also notorious in some circles for what is described as her “myth-making” ability. One that has been called into question by professional historians is her claim that Esther Hobart Morris had a “tea party” at her South Pass City home to persuade local legislators to introduce a woman’s suffrage bill in 1869. The Act passed in the Territorial Assembly, and was introduced by a man from South Pass, but apparently the tea party never happened.

Morris herself (who lived until 1902) never claimed to be the one who promoted the suffrage bill. A man who said he was at the tea party, Colonel H.G. Nickerson, later became president of the Oregon Trail Commission and a friend of Dr. Hebard’s. He might have concocted the myth to please Hebard, or he had other reasons for inventing the story around 1916, nearly 50 years after the event happened.

That myth is still perpetuated by the Architect of the U.S. Capitol’s on-line description of Morris’ statue representing Wyoming that was placed in “Statuary Hall” in 1960. The same statue is in front of the Wyoming Capitol. As Wyoming State Historical Society member Kim Viner points out, a better way to honor Morris is to say that she was the first woman to benefit from the passage of the Suffrage Act because the Act also gave women the right to hold office. That allowed Morris to be appointed a Justice of the Peace for South Pass City in early 1870—the first woman in Wyoming to hold an office. But as Viner and many other historians claim, she was not a major player in territorial women’s suffrage.

Sacagawea Myth

Another Hebard “myth” is that the famous Shoshone Indian guide Sacagawea of the Lewis and Clark Expedition died around age 95 in Wyoming. Hebard saw to it that a monument to her was erected at Fort Washakie claiming that her death was in 1884.

Another monument is at Mobridge, South Dakota where most historians say she more likely died at age 24 in 1812. Hebard put all her faith in stories that were relayed to her by natives and a missionary on the Wind River Reservation. Fact-checkers have been able to show that their oral histories were wishful thinking on the part of those who gave the testimony.

Erecting historical markers was another of her passions—she teamed with Edward Ivinson to see to it that a monument capped by a splendid eagle was erected to honor all who served in WW I from Laramie and UW. The monument first stood in the center of the intersection of Ivinson (then Thornburgh) and Second Streets, but has been moved to the northeast corner of the courthouse block. She did all the work to gather the names, not so easy a task then as it would be today, and Ivinson paid for it.

The “Doctor’s Inn”

Hebard and her housemate Dr. Agnes Wergeland built a house at 318 S. 10th St. in Laramie, which became known with affection as “The Doctor’s Inn.” Norwegian born Dr. Wergeland received a Ph. D. in history from the University of Zurich in 1890. She came to UW in 1902 and taught at UW until her death in 1914 at age 57. Hebard’s retired sister Alice, who had been a schoolteacher in Laramie County, then moved in with Hebard until her death in 1928. In 1931, Hebard retired.

When Hebard died in Laramie at age 75 in 1936, Carrie Chapman Catt attended her services at UW and said that she was “a giant in the effort to achieve women’s suffrage in the west.” Hers was one of the largest memorial services ever in the UW auditorium. In an act typical of her, Hebard gave space at her plot in Laramie’s Greenhill Cemetery for the burial of Charles Bocker in 1929, an indigent fellow who told of being an early pioneer in what is now Albany County. His tombstone, probably paid for by Hebard, gives a full account of the adventures in his life as a teamster. Her tombstone, by contrast, contains only her name and the dates of her life.

By Judy Knight

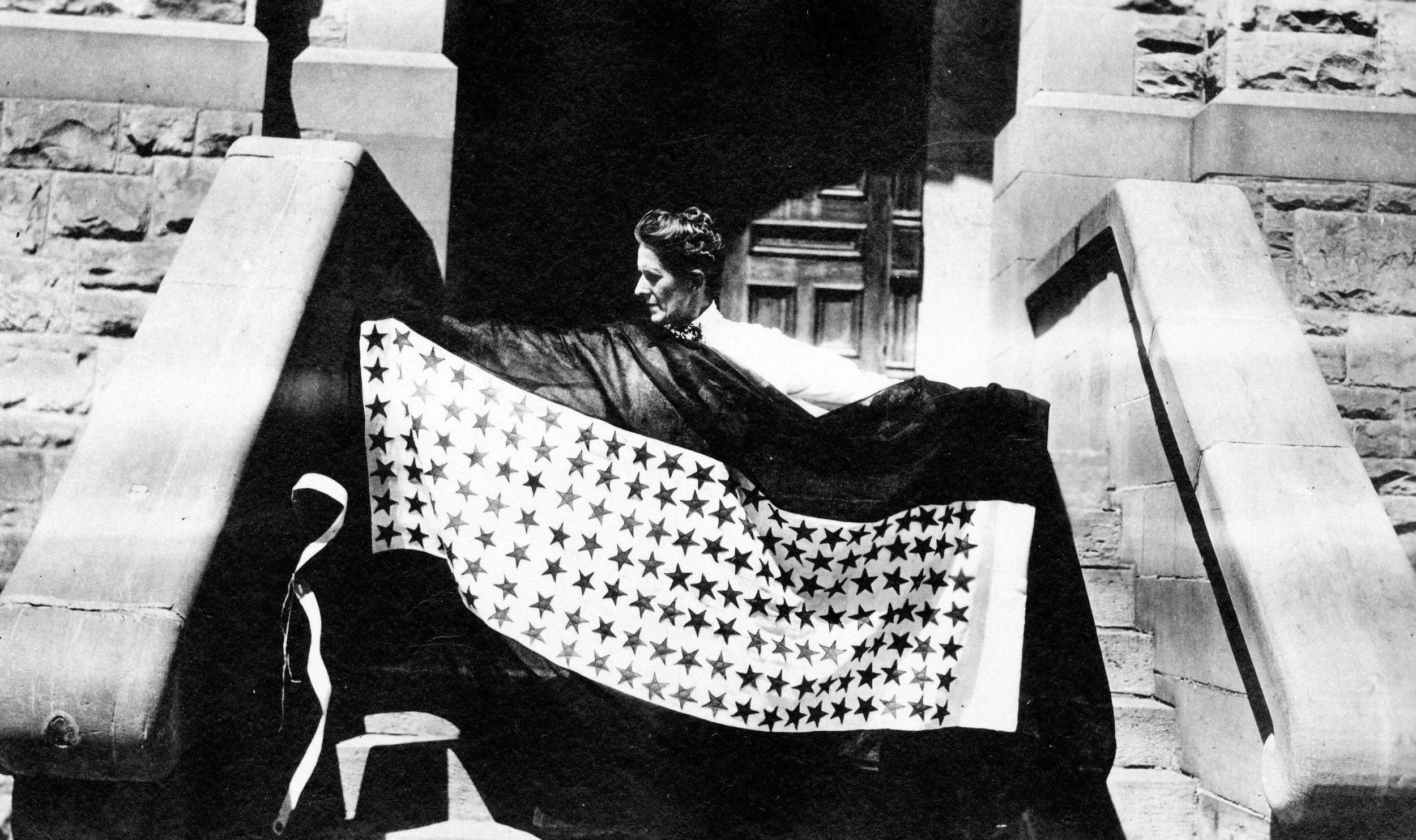

Caption: Grace Raymond Hebard strikes a dramatic pose with patriotic bunting on the steps of Old Main at UW. Edith Stirling Johnson, one of her student staff assistants at the UW Library when Hebard was the Librarian, may have taken the undated snapshot; Melvin Johnson, Edith’s son, donated it.

Source: Melvin Johnson Collection, Laramie Plains Museum

Caption: Dr. Hebard in academic robes, undated photo taken after 1893.

Source: Laramie Plains Museum